Level Set: DIY vs. Delegation

Stepping back and taking your hands off the wheel is hard.

A Type-A mentality spreads across all facets of life, from our careers to household management, from the best travel route to what we’re having for dinner.

However, one aspect of our lives is best left untouched and left to professionals: financial and investment management.

Do-it-yourself (DIY) investors consistently underperform markets to a shocking degree, risking long-term economic health and retirement. Yet, many still think that the law of averages doesn’t apply to them. This is a mistake – a costly one.

Deployed tax-advantaged investment management strategies that optimized a client’s portfolio well beyond their household benchmarks

Numbers Don't Lie

People are tricky. Though nearly every retail investor will acknowledge that, on average, individual investment strategies underperform broad investment benchmark indices (like the S&P 500) over a long-term investment cycle, the same active retail investors nearly always think, “Yeah, but not me.”

Most of us can relate to that mindset in some capacity, if not strictly in terms of investment performance. The tendency to overestimate our abilities compared to the average “other” or group collective is called illusory superiority and isn’t a character flaw but a fact of our cognitive heuristics.

But the data doesn’t lie.

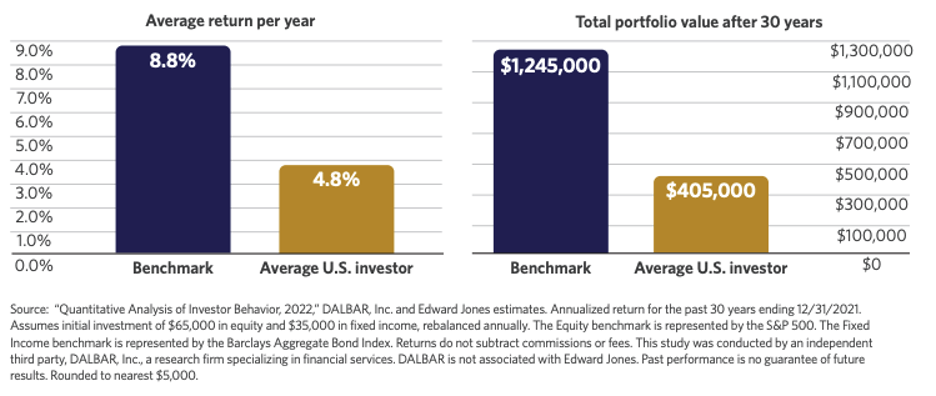

Average US investors’ returns tend to be nearly half that of broader index benchmarks annually. Throughout a 30-year cycle, an index-based portfolio is worth more than 3x that of a typical investor.

The reasons are varied, and we’ll look at them in a moment, but for now, step back and consider this: even if you’re convinced that your select strategy or stock picks are an exception to the rule, is it worth risking your retirement – or the opportunity to pass on generational wealth?

Proper Preparation = Poor Performance?

We looked at one reason behind DIY investor underperformance—the illusory superiority cognitive bias—but there are myriad other reasons for widespread retail underperformance, ranging from nuts-and-bolts mechanisms to further psychological follies and broader systemic issues that many tend to overlook.

While not exhaustive, these tend to be some of the most common reasons that DIY investors rarely match the market and, more often than not, represent a confluence of factors acting as a “perfect storm” putting your retirement and long-term financial health at risk.

Active Trading

While today’s brokerages and digital accessibility make DIY investing easy and cheap compared to years past, when investors called in trade orders to a broker and often paid steep commission fees, ease of access comes with an apparent downside: the simpler it is to trade and tweak your portfolio, the more likely you are to do so.

Tweaking, fiddling, and adjusting asset allocations without sticking to a plan and long-term strategy is likely the primary reason DIY investors underperform in the long run. This is due, in part, to the disposition effect. The disposition effect describes a common tendency for traders to take profits early and often rather than let “winning stocks” continue to perform while holding on to losing stocks in the hope they’ll soon rebound. In the latter case, it’s closely related to the sunk cost fallacy.

As investing legend Peter Lynch put it, “Selling your winners and holding your losers is like cutting the flowers and watering the weeds.” Unfortunately, we all tend to be very poor gardeners when it comes to DIY investing.

The FOMO Effect

Upset you missed the boat on Nvidia or any other recent example of a high-flying tech stock generating massive gains?

Overenthusiasm and exuberance tend to fuel the “FOMO (fear of missing out) Effect” that often sees investors staking substantial cash in a stock at or near all-time highs, only to effectively “buy the top” and never recover.

While it’s impossible to forecast the future accurately – Nvidia may climb another 25% over the next year, or it may crash and burn tomorrow – history is full of examples showing that fearful investors trying to ride a stock bandwagon often end up with portfolios full of poorly-performing companies and, of course, keeping those losing positions intact due to the disposition effect.

The past few years’ GameStop saga is one example, but there are many more. In fact, ask any active retail trader what their worst move was, and it will often be a poorly-timed investment driven by the FOMO Effect.

Signals and Noise

Today, there are nearly endless amounts of market and stock news and analysis, driven by mountains of data detailing everything from financial ratios and metrics to local weather effects on stock exchanges.

One would think easier access to data and trading signals would simplify retail trading, but the opposite tends to be the case: instead, many go too deeply into the weeds and end up overcomplicating a strategy in a bid to find the perfect mix of technical and fundamental indicators to predict market moves.

Worse yet, even the experts tend to introduce more noise than signal, whether intentionally or not.

For example:

Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman famously predicted

that “hell is coming” to the stock market in March 2020 during the pandemic’s early days. Holding multiple short positions (bets that the market would go down), Ackman made his prediction on CNBC before selling the positions a week later to go long – ultimately pocketing $2.6 billion on the short trade and capturing some of the market’s most significant gains throughout 2020 and 2021. How many DIY traders interpreted Ackman’s noise as a signal to go short and, in turn, missed out on a once-in-a-generation rally?

Likewise, many thought that a certain segment of stocks would continue

climbing indefinitely amid the pandemic, to the point of ignoring basic stock and company operation fundamentals. Though Peloton’s products are great, the company is (and was) operationally incompetent across the spectrum. Investors interpreting massive inflows into Peloton and predicting that its products would continue to be popular post-pandemic could have easily bought shares in the triple-digit range; the stock trades below $5 today.

Diversification (or lack thereof)

Diversification is an easy mantra to chant when strategizing a DIY portfolio, but it takes a lot of work to execute properly. This is due to a range of factors, the simplest being that “proper” diversification – anchored in modern portfolio theory – is highly technical and complex to understand, let alone implement.

Another common blow to diversification is the familiarity bias. This bias describes our tendency to stick with what we know, i.e., a physician may overweight healthcare stocks, or a financial services professional may stick to bank stocks. While there’s a benefit to investing in your area of expertise, it also exposes you to sector risk that, undiversified, can tank your portfolio.

The familiarity bias is even at play at a macro level – most US-based investors tend to stick to US-based stocks, even though international and emerging market diversification reduces overall risk while offering additional upside.

Expert Decisions Without The Time Investment

Top-tier financial professionals deliver:

To head off a common misconception about hiring and working with a financial professional, the relationship’s value isn’t tied strictly to portfolio performance. While it’s a component, tropes like “Most asset managers can’t even beat the market” take a short-sighted and ultimately myopic approach to value.

That’s because anchoring your conception of a financial professional’s value within an investment performance framework fails to capture the range of opportunities and financial interventions a well-rounded professional offers. In some cases, those interventions are only quantifiable in retrospect – it’s hard, for example, to quantify the benefit of comprehensive estate planning on your family in the event of a worst-case scenario.

Simply put, a financial professional has the access and expertise to open new financial intervention opportunities, some of which (like diversified asset classes and alternative investments) are actually off-limits to retail investors.

Tax optimization tools: Tax code is complex, and often, high earners (at least, those not working within financial services themselves) don’t know how to best manage their strategy in a way that reduces total tax paid. These opportunities vary but, beyond standard nuts-and-bolts filings, can include:

Ideal asset location management: Different assets play by different tax rules, and a financial professional knows the nuanced playbook and how to maximize it to your benefit. From the simplest allocation, such as stacking municipal bonds in a taxable brokerage in place of Certificates of Deposit, to the more complex matters involving overseas incorporation, financial professionals well-versed in asset location management make a huge difference come tax time.

Tax loss harvesting strategies: Some see tax loss harvesting as a “runner-up” prize to realized gains, but advanced strategies pay dividends over an investment cycle by slashing net tax exposure and limiting negative long-term, compounding effects of unrealized gains.

Roth conversions: A key retirement planning strategy for high earners, Roth conversions are complex processes but one that financial professionals execute often. A Roth conversion helps slash taxes owed in retirement, letting you proactively maximize later-life cash flow and preemptively budget for contingencies or luxuries. As with many maneuvers of this type, doing so is complex, with an entire rulebook dictating the process, creating risk for those going it alone without prior experience.

And more – while offerings vary by financial service provider, most offer a full suite of services you may not realize you need and that, combined, bring enough value to the table to pay for themselves many times over.

When it comes to taxes, you don’t know what you don’t know—but tax law is nuanced and daunting. The price of not knowing can be astronomical, and even minor mistakes can compound rapidly.